Following on from my

last post, I have recently been using the

BayesOpt library to optimise my planned neural net, and this post is a brief outline, with code, of what I have been doing.

My intent was to design a

Nonlinear autoregressive exogenous model using my

currency strength indicator as the main exogenous input, along with other features derived from the use of

Savitzky-Golay filter convolution to model velocity, acceleration etc. I decided that rather than model prices directly, I would model the 20 period

simple moving average because it would seem reasonable to assume that modelling a smooth function would be easier, and from this average it is a trivial matter to reverse engineer to get to the underlying price.

Given that my projected feature space/lookback length/number of nodes combination is/was a triple digit, discrete dimensional problem, I used the "bayesoptdisc" function from the BayesOpt library to perform a discrete Bayesian optimisation over these parameters, the main

Octave script for this being shown below.

clear all ;

% load the data

% load eurusd_daily_bin_bars ;

% load gbpusd_daily_bin_bars ;

% load usdchf_daily_bin_bars ;

load usdjpy_daily_bin_bars ;

load all_rel_strengths_non_smooth ;

% all_rel_strengths_non_smooth = [ usd_rel_strength_non_smooth eur_rel_strength_non_smooth gbp_rel_strength_non_smooth chf_rel_strength_non_smooth ...

% jpy_rel_strength_non_smooth aud_rel_strength_non_smooth cad_rel_strength_non_smooth ] ;

% extract relevant data

% price = ( eurusd_daily_bars( : , 3 ) .+ eurusd_daily_bars( : , 4 ) ) ./ 2 ; % midprice

% price = ( gbpusd_daily_bars( : , 3 ) .+ gbpusd_daily_bars( : , 4 ) ) ./ 2 ; % midprice

% price = ( usdchf_daily_bars( : , 3 ) .+ usdchf_daily_bars( : , 4 ) ) ./ 2 ; % midprice

price = ( usdjpy_daily_bars( : , 3 ) .+ usdjpy_daily_bars( : , 4 ) ) ./ 2 ; % midprice

base_strength = all_rel_strengths_non_smooth( : , 1 ) .- 0.5 ;

term_strength = all_rel_strengths_non_smooth( : , 5 ) .- 0.5 ;

% clear unwanted data

% clear eurusd_daily_bars all_rel_strengths_non_smooth ;

% clear gbpusd_daily_bars all_rel_strengths_non_smooth ;

% clear usdchf_daily_bars all_rel_strengths_non_smooth ;

clear usdjpy_daily_bars all_rel_strengths_non_smooth ;

global start_opt_line_no = 200 ;

global stop_opt_line_no = 7545 ;

% get matrix coeffs

slope_coeffs = generalised_sgolay_filter_coeffs( 5 , 2 , 1 ) ;

accel_coeffs = generalised_sgolay_filter_coeffs( 5 , 2 , 2 ) ;

jerk_coeffs = generalised_sgolay_filter_coeffs( 5 , 3 , 3 ) ;

% create features

sma20 = sma( price , 20 ) ;

global targets = sma20 ;

[ sma_max , sma_min ] = adjustable_lookback_max_min( sma20 , 20 ) ;

global sma20r = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20slope = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20accel = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20jerk = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20diffs = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20diffslope = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20diffaccel = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global sma20diffjerk = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global base_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

global term_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

base_term_osc = base_strength .- term_strength ;

global base_term_osc_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

slope_bt_osc = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_term_osc , 5 , 2 , 1 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global slope_bt_osc_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

accel_bt_osc = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_term_osc , 5 , 2 , 2 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global accel_bt_osc_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

jerk_bt_osc = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_term_osc , 5 , 3 , 3 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global jerk_bt_osc_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

slope_base_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_strength , 5 , 2 , 1 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global slope_base_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

accel_base_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_strength , 5 , 2 , 2 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global accel_base_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

jerk_base_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( base_strength , 5 , 3 , 3 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global jerk_base_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

slope_term_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( term_strength , 5 , 2 , 1 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global slope_term_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

accel_term_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( term_strength , 5 , 2 , 2 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global accel_term_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

jerk_term_strength = rolling_endpoint_gen_poly_output( term_strength , 5 , 3 , 3 ) ; % no_of_points(p),filter_order(n),derivative(s)

global jerk_term_strength_f = zeros( size(sma20,1) , 5 ) ;

min_max_range = sma_max .- sma_min ;

for ii = 51 : size( sma20 , 1 ) - 1 % one step ahead is target

targets(ii) = 2 * ( ( sma20(ii+1) - sma_min(ii) ) / min_max_range(ii) - 0.5 ) ;

% scaled sma20

sma20r(ii,:) = 2 .* ( ( flipud( sma20(ii-4:ii,1) )' .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) ;

sma20slope(ii,:) = fliplr( ( 2 .* ( ( sma20(ii-4:ii,1)' .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) ) * slope_coeffs ) ;

sma20accel(ii,:) = fliplr( ( 2 .* ( ( sma20(ii-4:ii,1)' .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) ) * accel_coeffs ) ;

sma20jerk(ii,:) = fliplr( ( 2 .* ( ( sma20(ii-4:ii,1)' .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) ) * jerk_coeffs ) ;

% scaled diffs of sma20

sma20diffs(ii,:) = fliplr( diff( 2.* ( ( sma20(ii-5:ii,1) .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) )' ) ;

sma20diffslope(ii,:) = fliplr( diff( 2.* ( ( sma20(ii-5:ii,1) .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) )' * slope_coeffs ) ;

sma20diffaccel(ii,:) = fliplr( diff( 2.* ( ( sma20(ii-5:ii,1) .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) )' * accel_coeffs ) ;

sma20diffjerk(ii,:) = fliplr( diff( 2.* ( ( sma20(ii-5:ii,1) .- sma_min(ii) ) ./ min_max_range(ii) .- 0.5 ) )' * jerk_coeffs ) ;

% base strength

base_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( base_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

slope_base_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( slope_base_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

accel_base_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( accel_base_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

jerk_base_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( jerk_base_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

% term strength

term_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( term_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

slope_term_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( slope_term_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

accel_term_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( accel_term_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

jerk_term_strength_f(ii,:) = fliplr( jerk_term_strength(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

% base term oscillator

base_term_osc_f(ii,:) = fliplr( base_term_osc(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

slope_bt_osc_f(ii,:) = fliplr( slope_bt_osc(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

accel_bt_osc_f(ii,:) = fliplr( accel_bt_osc(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

jerk_bt_osc_f(ii,:) = fliplr( jerk_bt_osc(ii-4:ii)' ) ;

endfor

% create xset for bayes routine

% raw indicator

xset = zeros( 4 , 5 ) ; xset( 1 , : ) = 1 : 5 ;

% add the slopes

to_add = zeros( 4 , 15 ) ;

to_add( 1 , : ) = [ 1 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 ] ;

to_add( 2 , : ) = [ 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 ] ;

xset = [ xset to_add ] ;

% add accels

to_add = zeros( 4 , 21 ) ;

to_add( 1 , : ) = [ 1 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 ] ;

to_add( 2 , : ) = [ 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 3 3 3 1 2 3 4 2 3 3 4 4 4 4 ] ;

to_add( 3 , : ) = [ 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 1 1 1 2 2 3 1 2 3 4 ] ;

xset = [ xset to_add ] ;

% add jerks

to_add = zeros( 4 , 70 ) ;

to_add( 1 , : ) = [ 1 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 ] ;

to_add( 2 , : ) = [ 1 1 2 2 2 1 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 1 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 1 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 ] ;

to_add( 3 , : ) = [ 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 3 3 3 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 3 3 3 1 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 1 1 2 2 1 2 2 3 3 3 1 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 1 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 5 ] ;

to_add( 4 , : ) = [ 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 1 1 2 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 1 2 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 1 2 3 4 5 ] ;

xset = [ xset to_add ] ;

% construct all_xset for combinations of indicators and look back lengths

all_zeros = zeros( size( xset ) ) ;

all_xset = [ xset ; repmat( all_zeros , 3 , 1 ) ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; xset ; all_zeros ; all_zeros ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; all_zeros ; xset ; all_zeros ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; all_zeros ; all_zeros ; xset ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; xset ; xset ; all_zeros ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; xset ; all_zeros ; xset ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset [ xset ; all_zeros ; xset ; xset ] ] ;

all_xset = [ all_xset repmat( xset , 4 , 1 ) ] ;

ones_all_xset = ones( 1 , size( all_xset , 2 ) ) ;

% now add layer for number of neurons and extend as necessary

max_number_of_neurons_in_layer = 20 ;

parameter_matrix = [] ;

for ii = 2 : max_number_of_neurons_in_layer % min no. of neurons is 2, max = max_number_of_neurons_in_layer

parameter_matrix = [ parameter_matrix [ ii .* ones_all_xset ; all_xset ] ] ;

endfor

% now the actual bayes optimisation routine

% set the parameters

params.n_iterations = 190; % bayesopt library default is 190

params.n_init_samples = 10;

params.crit_name = 'cEIa'; % cEI is default. cEIa is an annealed version

params.surr_name = 'sStudentTProcessNIG';

params.noise = 1e-6;

params.kernel_name = 'kMaternARD5';

params.kernel_hp_mean = [1];

params.kernel_hp_std = [10];

params.verbose_level = 1; % 3 to path below

params.log_filename = '/home/dekalog/Documents/octave/cplusplus.oct_functions/nn_functions/optimise_narx_ind_lookback_nodes_log';

params.l_type = 'L_MCMC' ; % L_EMPIRICAL is default

params.epsilon = 0.5 ; % probability of performing a random (blind) evaluation of the target function.

% Higher values implies forced exploration while lower values relies more on the exploration/exploitation policy of the criterion. 0 is default

% the function to optimise

fun = 'optimise_narx_ind_lookback_nodes_rolling' ;

% the call to the Bayesopt library function

bayesoptdisc( fun , parameter_matrix , params ) ;

% result is the minimum as a vector (x_out) and the value of the function at the minimum (y_out)

What this script basically does is:

- load all the relevant data ( in this case a forex pair )

- creates a set of scaled features

- creates a necessary parameter matrix for the discrete optimisation function

- sets the parameters for the optimisation routine

- and finally calls the "bayesoptdisc" function

Note that in step 2 all the features are declared as global variables, this being necessary because the "bayesoptdisc" function of the BayesOpt library does not appear to admit passing these variables as inputs to the function.

The actual function to be optimised is given in the following code box, and is basically a looped neural net training routine.

## Copyright (C) 2017 dekalog

##

## This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it

## under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by

## the Free Software Foundation; either version 3 of the License, or

## (at your option) any later version.

##

## This program is distributed in the hope that it will be useful,

## but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of

## MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the

## GNU General Public License for more details.

##

## You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License

## along with this program. If not, see .

## -*- texinfo -*-

## @deftypefn {} {@var{retval} =} optimise_narx_ind_lookback_nodes_rolling (@var{input1})

##

## @seealso{}

## @end deftypefn

## Author: dekalog

## Created: 2017-03-21

function [ retval ] = optimise_narx_ind_lookback_nodes_rolling( input1 )

% declare all the global variables so the function can "see" them

global start_opt_line_no ;

global stop_opt_line_no ;

global targets ;

global sma20r ; % 2

global sma20slope ;

global sma20accel ;

global sma20jerk ;

global sma20diffs ;

global sma20diffslope ;

global sma20diffaccel ;

global sma20diffjerk ;

global base_strength_f ;

global slope_base_strength_f ;

global accel_base_strength_f ;

global jerk_base_strength_f ;

global term_strength_f ;

global slope_term_strength_f ;

global accel_term_strength_f ;

global jerk_term_strength_f ;

global base_term_osc_f ;

global slope_bt_osc_f ;

global accel_bt_osc_f ;

global jerk_bt_osc_f ;

% build feature matrix from the above global variable according to parameters in input1

hidden_layer_size = input1(1) ;

% training targets

Y = targets( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1 ) ;

% create empty feature matrix

X = [] ;

% which will always have at least one element of the main price series for the NARX

X = [ X sma20r( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(2) ) ] ;

% go through input1 values in turn and add to X if necessary

if input1(3) > 0

X = [ X sma20slope( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(3) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(4) > 0

X = [ X sma20accel( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(4) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(5) > 0

X = [ X sma20jerk( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(5) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(6) > 0

X = [ X sma20diffs( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(6) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(7) > 0

X = [ X sma20diffslope( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(7) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(8) > 0

X = [ X sma20diffaccel( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(8) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(9) > 0

X = [ X sma20diffjerk( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(9) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(10) > 0 % input for base and term strengths together

X = [ X base_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(10) ) ] ;

X = [ X term_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(10) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(11) > 0

X = [ X slope_base_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(11) ) ] ;

X = [ X slope_term_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(11) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(12) > 0

X = [ X accel_base_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(12) ) ] ;

X = [ X accel_term_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(12) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(13) > 0

X = [ X jerk_base_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(13) ) ] ;

X = [ X jerk_term_strength_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(13) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(14) > 0

X = [ X base_term_osc_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(14) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(15) > 0

X = [ X slope_bt_osc_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(15) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(16) > 0

X = [ X accel_bt_osc_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(16) ) ] ;

endif

if input1(17) > 0

X = [ X jerk_bt_osc_f( start_opt_line_no:stop_opt_line_no , 1:input1(17) ) ] ;

endif

% now the X features matrix has been formed, get its size

X_rows = size( X , 1 ) ; X_cols = size( X , 2 ) ;

X = [ ones( X_rows , 1 ) X ] ; % add bias unit to X

fan_in = X_cols + 1 ; % no. of inputs to a node/unit, including bias

fan_out = 1 ; % no. of outputs from node/unit

r = sqrt( 6 / ( fan_in + fan_out ) ) ;

rolling_window_length = 100 ;

n_iters = 100 ;

n_iter_errors = zeros( n_iters , 1 ) ;

all_errors = zeros( X_rows - ( rolling_window_length - 1 ) - 1 , 1 ) ;

rolling_window_loop_iter = 0 ;

for rolling_window_loop = rolling_window_length : X_rows - 1

rolling_window_loop_iter = rolling_window_loop_iter + 1 ;

% train n_iters no. of nets and put the error stats in n_iter_errors

for ii = 1 : n_iters

% initialise weights

% see https://stats.stackexchange.com/questions/47590/what-are-good-initial-weights-in-a-neural-network

% One option is Orthogonal random matrix initialization for input_to_hidden weights

% w_i = rand( X_cols + 1 , hidden_layer_size ) ;

% [ u , s , v ] = svd( w_i ) ;

% input_to_hidden = [ ones( X_rows , 1 ) X ] * u ; % adding bias unit to X

% using fan_in and fan_out for tanh

w_i = ( rand( X_cols + 1 , hidden_layer_size ) .* ( 2 * r ) ) .- r ;

input_to_hidden = X( rolling_window_loop - ( rolling_window_length - 1 ) : rolling_window_loop , : ) * w_i ;

% push the input_to_hidden through the chosen sigmoid function

hidden_layer_output = sigmoid_lecun_m( input_to_hidden ) ;

% add bias unit for the output from hidden

hidden_layer_output = [ ones( rolling_window_length , 1 ) hidden_layer_output ] ;

% use hidden_layer_output as the input to a linear regression fit to targets Y

% a la Extreme Learning Machine

% w = ( inv( X' * X ) * X' ) * y ; the "classic" way for linear regression, where

% X = hidden_layer_output, but

w = ( ( hidden_layer_output' * hidden_layer_output ) \ hidden_layer_output' ) * Y( rolling_window_loop - ( rolling_window_length - 1 ) : rolling_window_loop , 1 ) ;

% is quicker and recommended

% use these current values of w_i and w for out of sample test

os_input_to_hidden = X( rolling_window_loop + 1 , : ) * w_i ;

os_hidden_layer_output = sigmoid_lecun_m( os_input_to_hidden ) ;

os_hidden_layer_output = [ 1 os_hidden_layer_output ] ; % add bias

os_output = os_hidden_layer_output * w ;

n_iter_errors( n_iters ) = abs( Y( rolling_window_loop + 1 , 1 ) - os_output ) ;

endfor

all_errors( rolling_window_loop_iter ) = mean( n_iter_errors ) ;

endfor % rolling_window_loop

retval = mean( all_errors ) ;

clear X w_i ;

endfunction

However, to speed things up for some rapid prototyping, rather than use

backpropagation training this function uses the principles of an

extreme learning machine and loops over 100 such trained ELMs per set of features contained in a rolling window of length 100 across the entire training data set.

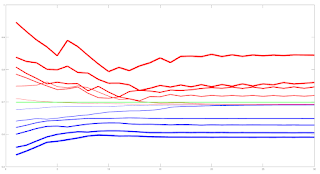

Walk forward cross validation is performed for each of the 100 ELMs, an average of the out of sample error obtained, and these averages across the whole data set are then averaged to provide the function return. The code was run on daily bars of the four major

forex pairs; EURUSD, GBPUSD, USDCHF and USDYPY.

The results of running the above are quite interesting. The first surprise is that the currency strength indicator and features derived from it were not included in the optimal model for any of the four tested pairs. Secondly, for all pairs, a scaled version of a 20 bar price momentum function, and derived features, was included in the optimal model. Finally, again for all pairs, there was a symmetrically decreasing lookback period across the selected features, and when averaged across all pairs the following pattern results: 10 3 3 2 1 3 3 2 1, which is to be read as:

- 10 nodes (plus a bias node) in the hidden layer

- lookback length of 3 for the scaled values of the SMA20 and the 20 bar scaled momentum function

- lookback length of 3 for the slopes/rates of change of the above

- lookback length of 2 for the "accelerations" of the above

- lookback length of 1 for the "jerks" of the above

So it would seem that the 20 bar momentum function is a better exogenous input than the currency strength indicator. The symmetry across features is quite pleasing, and the selection of these "

physical motion" features across all the tested pairs tends to confirm their validity. The fact that the currency strength indicator was not selected does not mean that this indicator is of no value, but perhaps it should not be used for regression purposes, but rather as a filter. More in due course.