As a prelude to the tests mentioned in my previous post it has been necessary to write code to randomly permute price data, and in the code box below is the

Octave .oct file I have written to do this.

#include octave oct.h

#include octave dcolvector.h

#include math.h

#include algorithm

#include "MersenneTwister.h"

DEFUN_DLD (randomised_price_data, args, , "Inputs are OHLC column vectors and tick size. Output is permuted synthetic OHLC")

{

octave_value_list retval_list ;

int nargin = args.length () ;

int vec_length = args(0).length () - 1 ;

if ( nargin != 5 )

{

error ("Invalid arguments. Inputs are OHLC column vectors and tick size.") ;

return retval_list ;

}

if (args(0).length () < 50)

{

error ("Invalid arguments. Inputs are OHLC column vectors and tick size.") ;

return retval_list ;

}

if (error_state)

{

error ("Invalid arguments. Inputs are OHLC column vectors and tick size.") ;

return retval_list ;

}

ColumnVector open = args(0).column_vector_value () ; // open vector

ColumnVector high = args(1).column_vector_value () ; // high vector

ColumnVector low = args(2).column_vector_value () ; // low vector

ColumnVector close = args(3).column_vector_value () ; // close vector

double tick = args(4).double_value(); // Tick size

//double trend_increment = ( close ( args(3).length () - 1 ) - close (0) ) / ( args(3).length () - 1 ) ;

ColumnVector open_change_var ( vec_length ) ;

ColumnVector high_change_var ( vec_length ) ;

ColumnVector low_change_var ( vec_length ) ;

ColumnVector close_change_var ( vec_length ) ;

// variables for shuffling

double temp ;

int k1 ;

int k2 ;

// Check for negative or zero price values due to continuous back- adjusting of price series & compensate if necessary

// Note: the "&" below acts as Address-of operator: p = &x; Read: Assign to p (a pointer) the address of x.

double lowest_low = *std::min_element( &low(0), &low(low.length()) ) ;

double correction_factor = 0.0 ;

if ( lowest_low <= 0.0 )

{

correction_factor = fabs(lowest_low) + tick;

for (octave_idx_type ii (0); ii < args(0).length (); ii++)

{

open (ii) = open (ii) + correction_factor;

high (ii) = high (ii) + correction_factor;

low (ii) = low (ii) + correction_factor;

close (ii) = close (ii) + correction_factor;

}

}

// fill the change vectors with their values

for ( octave_idx_type ii (1) ; ii < args(0).length () ; ii++ )

{

// comment out/uncomment depending on whether to include a relationship to previous bar's volatility or not

// No relationship

// open_change_var (ii-1) = log10( open (ii) / close (ii) ) ;

// high_change_var (ii-1) = log10( high (ii) / close (ii) ) ;

// low_change_var (ii-1) = log10( low (ii) / close (ii) ) ;

// some relationship

open_change_var (ii-1) = ( close (ii) - open (ii) ) / ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) ;

high_change_var (ii-1) = ( close (ii) - high (ii) ) / ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) ;

low_change_var (ii-1) = ( close (ii) - low (ii) ) / ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) ;

close_change_var (ii-1) = log10( close(ii) / close(ii-1) ) ;

}

// Shuffle the log vectors

MTRand mtrand1 ; // Declare the Mersenne Twister Class - will seed from system time

k1 = vec_length - 1 ; // initialise prior to shuffling

while ( k1 > 0 ) // While at least 2 left to shuffle

{

k2 = mtrand1.randInt( k1 ) ; // Pick an int from 0 through k1

if ( k2 > k1 ) // check if random vector index no. k2 is > than max vector index - should never happen

{

k2 = k1 - 1 ; // But this is cheap insurance against disaster if it does happen

}

temp = open_change_var (k1) ; // allocate the last vector index content to temp

open_change_var (k1) = open_change_var (k2) ; // allocate random pick to the last vector index

open_change_var (k2) = temp ; // allocate temp content to old vector index position of random pick

temp = high_change_var (k1) ; // allocate the last vector index content to temp

high_change_var (k1) = high_change_var (k2) ; // allocate random pick to the last vector index

high (k2) = temp ; // allocate temp content to old vector index position of random pick

temp = low_change_var (k1) ; // allocate the last vector index content to temp

low_change_var (k1) = low_change_var (k2) ; // allocate random pick to the last vector index

low_change_var (k2) = temp ; // allocate temp content to old vector index position of random pick

temp = close_change_var (k1) ; // allocate the last vector index content to temp

close_change_var (k1) = close_change_var (k2) ; // allocate random pick to the last vector index

close_change_var (k2) = temp ; // allocate temp content to old vector index position of random pick

k1 = k1 - 1 ; // count down

} // Shuffling is complete when this while loop exits

// create the new shuffled price series and round to nearest tick

for ( octave_idx_type ii (1) ; ii < args(0).length () ; ii++ )

{

close (ii) = ( floor( ( close (ii-1) * pow( 10, close_change_var(ii-1) ) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

// comment out/uncomment depending on whether to include a relationship to previous bar's volatility or not

// no relationship

// open (ii) = ( floor( ( close (ii) * pow( 10, open_change_var(ii-1) ) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

// high (ii) = ( floor( ( close (ii) * pow( 10, high_change_var(ii-1) ) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

// low (ii) = ( floor( ( close (ii) * pow( 10, low_change_var(ii-1) ) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

// some relationship

open (ii) = ( floor( ( open_change_var(ii-1) * ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) + close (ii) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

high (ii) = ( floor( ( high_change_var(ii-1) * ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) + close (ii) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

low (ii) = ( floor( ( low_change_var(ii-1) * ( high (ii-1) - low (ii-1) ) + close (ii) ) / tick + 0.5 ) ) * tick ;

}

// if compensation due to negative or zero original price values due to continuous back- adjusting of price series took place, re-adjust

if ( correction_factor != 0.0 )

{

for ( octave_idx_type ii (0); ii < args(0).length () ; ii++ )

{

open (ii) = open (ii) - correction_factor ;

high (ii) = high (ii) - correction_factor ;

low (ii) = low (ii) - correction_factor ;

close (ii) = close (ii) - correction_factor ;

}

}

retval_list (3) = close ;

retval_list (2) = low ;

retval_list (1) = high ;

retval_list (0) = open ;

return retval_list ;

} // end of function

The function can be compiled in two slightly different versions by commenting/commenting out some indicated code:- this makes it possible to choose between having more or less dependency between adjacent bars based on the range of the first bar. For completeness the required header file for the Mersenne Twister algorithm is given next

// MersenneTwister.h

// Mersenne Twister random number generator -- a C++ class MTRand

// Based on code by Makoto Matsumoto, Takuji Nishimura, and Shawn Cokus

// Richard J. Wagner v1.1 28 September 2009 wagnerr@umich.edu

// The Mersenne Twister is an algorithm for generating random numbers. It

// was designed with consideration of the flaws in various other generators.

// The period, 2^19937-1, and the order of equidistribution, 623 dimensions,

// are far greater. The generator is also fast; it avoids multiplication and

// division, and it benefits from caches and pipelines. For more information

// see the inventors' web page at

// http://www.math.sci.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/~m-mat/MT/emt.html

// Reference

// M. Matsumoto and T. Nishimura, "Mersenne Twister: A 623-Dimensionally

// Equidistributed Uniform Pseudo-Random Number Generator", ACM Transactions on

// Modeling and Computer Simulation, Vol. 8, No. 1, January 1998, pp 3-30.

// Copyright (C) 1997 - 2002, Makoto Matsumoto and Takuji Nishimura,

// Copyright (C) 2000 - 2009, Richard J. Wagner

// All rights reserved.

//

// Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without

// modification, are permitted provided that the following conditions

// are met:

//

// 1. Redistributions of source code must retain the above copyright

// notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer.

//

// 2. Redistributions in binary form must reproduce the above copyright

// notice, this list of conditions and the following disclaimer in the

// documentation and/or other materials provided with the distribution.

//

// 3. The names of its contributors may not be used to endorse or promote

// products derived from this software without specific prior written

// permission.

//

// THIS SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED BY THE COPYRIGHT HOLDERS AND CONTRIBUTORS "AS IS"

// AND ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE

// IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE

// ARE DISCLAIMED. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT OWNER OR CONTRIBUTORS BE

// LIABLE FOR ANY DIRECT, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, SPECIAL, EXEMPLARY, OR

// CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES (INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, PROCUREMENT OF

// SUBSTITUTE GOODS OR SERVICES; LOSS OF USE, DATA, OR PROFITS; OR BUSINESS

// INTERRUPTION) HOWEVER CAUSED AND ON ANY THEORY OF LIABILITY, WHETHER IN

// CONTRACT, STRICT LIABILITY, OR TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE OR OTHERWISE)

// ARISING IN ANY WAY OUT OF THE USE OF THIS SOFTWARE, EVEN IF ADVISED OF THE

// POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

// The original code included the following notice:

//

// When you use this, send an email to: m-mat@math.sci.hiroshima-u.ac.jp

// with an appropriate reference to your work.

//

// It would be nice to CC: wagnerr@umich.edu and Cokus@math.washington.edu

// when you write.

#ifndef MERSENNETWISTER_H

#define MERSENNETWISTER_H

// Not thread safe (unless auto-initialization is avoided and each thread has

// its own MTRand object)

#include

#include

#include

#include

#include

class MTRand {

// Data

public:

typedef unsigned long uint32; // unsigned integer type, at least 32 bits

enum { N = 624 }; // length of state vector

enum { SAVE = N + 1 }; // length of array for save()

protected:

enum { M = 397 }; // period parameter

uint32 state[N]; // internal state

uint32 *pNext; // next value to get from state

int left; // number of values left before reload needed

// Methods

public:

MTRand( const uint32 oneSeed ); // initialize with a simple uint32

MTRand( uint32 *const bigSeed, uint32 const seedLength = N ); // or array

MTRand(); // auto-initialize with /dev/urandom or time() and clock()

MTRand( const MTRand& o ); // copy

// Do NOT use for CRYPTOGRAPHY without securely hashing several returned

// values together, otherwise the generator state can be learned after

// reading 624 consecutive values.

// Access to 32-bit random numbers

uint32 randInt(); // integer in [0,2^32-1]

uint32 randInt( const uint32 n ); // integer in [0,n] for n < 2^32

double rand(); // real number in [0,1]

double rand( const double n ); // real number in [0,n]

double randExc(); // real number in [0,1)

double randExc( const double n ); // real number in [0,n)

double randDblExc(); // real number in (0,1)

double randDblExc( const double n ); // real number in (0,n)

double operator()(); // same as rand()

// Access to 53-bit random numbers (capacity of IEEE double precision)

double rand53(); // real number in [0,1)

// Access to nonuniform random number distributions

double randNorm( const double mean = 0.0, const double stddev = 1.0 );

// Re-seeding functions with same behavior as initializers

void seed( const uint32 oneSeed );

void seed( uint32 *const bigSeed, const uint32 seedLength = N );

void seed();

// Saving and loading generator state

void save( uint32* saveArray ) const; // to array of size SAVE

void load( uint32 *const loadArray ); // from such array

friend std::ostream& operator<<( std::ostream& os, const MTRand& mtrand );

friend std::istream& operator>>( std::istream& is, MTRand& mtrand );

MTRand& operator=( const MTRand& o );

protected:

void initialize( const uint32 oneSeed );

void reload();

uint32 hiBit( const uint32 u ) const { return u & 0x80000000UL; }

uint32 loBit( const uint32 u ) const { return u & 0x00000001UL; }

uint32 loBits( const uint32 u ) const { return u & 0x7fffffffUL; }

uint32 mixBits( const uint32 u, const uint32 v ) const

{ return hiBit(u) | loBits(v); }

uint32 magic( const uint32 u ) const

{ return loBit(u) ? 0x9908b0dfUL : 0x0UL; }

uint32 twist( const uint32 m, const uint32 s0, const uint32 s1 ) const

{ return m ^ (mixBits(s0,s1)>>1) ^ magic(s1); }

static uint32 hash( time_t t, clock_t c );

};

// Functions are defined in order of usage to assist inlining

inline MTRand::uint32 MTRand::hash( time_t t, clock_t c )

{

// Get a uint32 from t and c

// Better than uint32(x) in case x is floating point in [0,1]

// Based on code by Lawrence Kirby (fred@genesis.demon.co.uk)

static uint32 differ = 0; // guarantee time-based seeds will change

uint32 h1 = 0;

unsigned char *p = (unsigned char *) &t;

for( size_t i = 0; i < sizeof(t); ++i )

{

h1 *= UCHAR_MAX + 2U;

h1 += p[i];

}

uint32 h2 = 0;

p = (unsigned char *) &c;

for( size_t j = 0; j < sizeof(c); ++j )

{

h2 *= UCHAR_MAX + 2U;

h2 += p[j];

}

return ( h1 + differ++ ) ^ h2;

}

inline void MTRand::initialize( const uint32 seed )

{

// Initialize generator state with seed

// See Knuth TAOCP Vol 2, 3rd Ed, p.106 for multiplier.

// In previous versions, most significant bits (MSBs) of the seed affect

// only MSBs of the state array. Modified 9 Jan 2002 by Makoto Matsumoto.

register uint32 *s = state;

register uint32 *r = state;

register int i = 1;

*s++ = seed & 0xffffffffUL;

for( ; i < N; ++i )

{

*s++ = ( 1812433253UL * ( *r ^ (*r >> 30) ) + i ) & 0xffffffffUL;

r++;

}

}

inline void MTRand::reload()

{

// Generate N new values in state

// Made clearer and faster by Matthew Bellew (matthew.bellew@home.com)

static const int MmN = int(M) - int(N); // in case enums are unsigned

register uint32 *p = state;

register int i;

for( i = N - M; i--; ++p )

*p = twist( p[M], p[0], p[1] );

for( i = M; --i; ++p )

*p = twist( p[MmN], p[0], p[1] );

*p = twist( p[MmN], p[0], state[0] );

left = N, pNext = state;

}

inline void MTRand::seed( const uint32 oneSeed )

{

// Seed the generator with a simple uint32

initialize(oneSeed);

reload();

}

inline void MTRand::seed( uint32 *const bigSeed, const uint32 seedLength )

{

// Seed the generator with an array of uint32's

// There are 2^19937-1 possible initial states. This function allows

// all of those to be accessed by providing at least 19937 bits (with a

// default seed length of N = 624 uint32's). Any bits above the lower 32

// in each element are discarded.

// Just call seed() if you want to get array from /dev/urandom

initialize(19650218UL);

register int i = 1;

register uint32 j = 0;

register int k = ( N > seedLength ? N : seedLength );

for( ; k; --k )

{

state[i] =

state[i] ^ ( (state[i-1] ^ (state[i-1] >> 30)) * 1664525UL );

state[i] += ( bigSeed[j] & 0xffffffffUL ) + j;

state[i] &= 0xffffffffUL;

++i; ++j;

if( i >= N ) { state[0] = state[N-1]; i = 1; }

if( j >= seedLength ) j = 0;

}

for( k = N - 1; k; --k )

{

state[i] =

state[i] ^ ( (state[i-1] ^ (state[i-1] >> 30)) * 1566083941UL );

state[i] -= i;

state[i] &= 0xffffffffUL;

++i;

if( i >= N ) { state[0] = state[N-1]; i = 1; }

}

state[0] = 0x80000000UL; // MSB is 1, assuring non-zero initial array

reload();

}

inline void MTRand::seed()

{

// Seed the generator with an array from /dev/urandom if available

// Otherwise use a hash of time() and clock() values

// First try getting an array from /dev/urandom

FILE* urandom = fopen( "/dev/urandom", "rb" );

if( urandom )

{

uint32 bigSeed[N];

register uint32 *s = bigSeed;

register int i = N;

register bool success = true;

while( success && i-- )

success = fread( s++, sizeof(uint32), 1, urandom );

fclose(urandom);

if( success ) { seed( bigSeed, N ); return; }

}

// Was not successful, so use time() and clock() instead

seed( hash( time(NULL), clock() ) );

}

inline MTRand::MTRand( const uint32 oneSeed )

{ seed(oneSeed); }

inline MTRand::MTRand( uint32 *const bigSeed, const uint32 seedLength )

{ seed(bigSeed,seedLength); }

inline MTRand::MTRand()

{ seed(); }

inline MTRand::MTRand( const MTRand& o )

{

register const uint32 *t = o.state;

register uint32 *s = state;

register int i = N;

for( ; i--; *s++ = *t++ ) {}

left = o.left;

pNext = &state[N-left];

}

inline MTRand::uint32 MTRand::randInt()

{

// Pull a 32-bit integer from the generator state

// Every other access function simply transforms the numbers extracted here

if( left == 0 ) reload();

--left;

register uint32 s1;

s1 = *pNext++;

s1 ^= (s1 >> 11);

s1 ^= (s1 << 7) & 0x9d2c5680UL;

s1 ^= (s1 << 15) & 0xefc60000UL;

return ( s1 ^ (s1 >> 18) );

}

inline MTRand::uint32 MTRand::randInt( const uint32 n )

{

// Find which bits are used in n

// Optimized by Magnus Jonsson (magnus@smartelectronix.com)

uint32 used = n;

used |= used >> 1;

used |= used >> 2;

used |= used >> 4;

used |= used >> 8;

used |= used >> 16;

// Draw numbers until one is found in [0,n]

uint32 i;

do

i = randInt() & used; // toss unused bits to shorten search

while( i > n );

return i;

}

inline double MTRand::rand()

{ return double(randInt()) * (1.0/4294967295.0); }

inline double MTRand::rand( const double n )

{ return rand() * n; }

inline double MTRand::randExc()

{ return double(randInt()) * (1.0/4294967296.0); }

inline double MTRand::randExc( const double n )

{ return randExc() * n; }

inline double MTRand::randDblExc()

{ return ( double(randInt()) + 0.5 ) * (1.0/4294967296.0); }

inline double MTRand::randDblExc( const double n )

{ return randDblExc() * n; }

inline double MTRand::rand53()

{

uint32 a = randInt() >> 5, b = randInt() >> 6;

return ( a * 67108864.0 + b ) * (1.0/9007199254740992.0); // by Isaku Wada

}

inline double MTRand::randNorm( const double mean, const double stddev )

{

// Return a real number from a normal (Gaussian) distribution with given

// mean and standard deviation by polar form of Box-Muller transformation

double x, y, r;

do

{

x = 2.0 * rand() - 1.0;

y = 2.0 * rand() - 1.0;

r = x * x + y * y;

}

while ( r >= 1.0 || r == 0.0 );

double s = sqrt( -2.0 * log(r) / r );

return mean + x * s * stddev;

}

inline double MTRand::operator()()

{

return rand();

}

inline void MTRand::save( uint32* saveArray ) const

{

register const uint32 *s = state;

register uint32 *sa = saveArray;

register int i = N;

for( ; i--; *sa++ = *s++ ) {}

*sa = left;

}

inline void MTRand::load( uint32 *const loadArray )

{

register uint32 *s = state;

register uint32 *la = loadArray;

register int i = N;

for( ; i--; *s++ = *la++ ) {}

left = *la;

pNext = &state[N-left];

}

inline std::ostream& operator<<( std::ostream& os, const MTRand& mtrand )

{

register const MTRand::uint32 *s = mtrand.state;

register int i = mtrand.N;

for( ; i--; os << *s++ << "\t" ) {}

return os << mtrand.left;

}

inline std::istream& operator>>( std::istream& is, MTRand& mtrand )

{

register MTRand::uint32 *s = mtrand.state;

register int i = mtrand.N;

for( ; i--; is >> *s++ ) {}

is >> mtrand.left;

mtrand.pNext = &mtrand.state[mtrand.N-mtrand.left];

return is;

}

inline MTRand to standard forms

// - Cleaned declarations and definitions to please Intel compiler

// - Revised twist() operator to work on ones'-complement machines

// - Fixed reload() function to work when N and M are unsigned

// - Added copy constructor and copy operator from Salvador Espana

followed by a file to show how to use this header file.

// example.cpp

// Examples of random number generation with MersenneTwister.h

// Richard J. Wagner 27 September 2009

#include iostream

#include fstream

#include "MersenneTwister.h"

using namespace std;

int main( int argc, char * const argv[] )

{

// A Mersenne Twister random number generator

// can be declared with a simple

MTRand mtrand1;

// and used with

double a = mtrand1();

// or

double b = mtrand1.rand();

cout << "Two real numbers in the range [0,1]: ";

cout << a << ", " << b << endl;

// Those calls produced the default of floating-point numbers

// in the range 0 to 1, inclusive. We can also get integers

// in the range 0 to 2^32 - 1 (4294967295) with

unsigned long c = mtrand1.randInt();

cout << "An integer in the range [0," << 0xffffffffUL;

cout << "]: " << c << endl;

// Or get an integer in the range 0 to n (for n < 2^32) with

int d = mtrand1.randInt( 42 );

cout << "An integer in the range [0,42]: " << d << endl;

// We can get a real number in the range 0 to 1, excluding

// 1, with

double e = mtrand1.randExc();

cout << "A real number in the range [0,1): " << e << endl;

// We can get a real number in the range 0 to 1, excluding

// both 0 and 1, with

double f = mtrand1.randDblExc();

cout << "A real number in the range (0,1): " << f << endl;

// The functions rand(), randExc(), and randDblExc() can

// also have ranges defined just like randInt()

double g = mtrand1.rand( 2.5 );

double h = mtrand1.randExc( 10.0 );

double i = 12.0 + mtrand1.randDblExc( 8.0 );

cout << "A real number in the range [0,2.5]: " << g << endl;

cout << "One in the range [0,10.0): " << h << endl;

cout << "And one in the range (12.0,20.0): " << i << endl;

// The distribution of numbers over each range is uniform,

// but it can be transformed to other useful distributions.

// One common transformation is included for drawing numbers

// in a normal (Gaussian) distribution

cout << "A few grades from a class with a 52 pt average ";

cout << "and a 9 pt standard deviation:" << endl;

for( int student = 0; student < 20; ++student )

{

double j = mtrand1.randNorm( 52.0, 9.0 );

cout << ' ' << int(j);

}

cout << endl;

// Random number generators need a seed value to start

// producing a sequence of random numbers. We gave no seed

// in our declaration of mtrand1, so one was automatically

// generated from the system clock (or the operating system's

// random number pool if available). Alternatively we could

// provide our own seed. Each seed uniquely determines the

// sequence of numbers that will be produced. We can

// replicate a sequence by starting another generator with

// the same seed.

MTRand mtrand2a( 1973 ); // makes new MTRand with given seed

double k1 = mtrand2a(); // gets the first number generated

MTRand mtrand2b( 1973 ); // makes an identical MTRand

double k2 = mtrand2b(); // and gets the same number

cout << "These two numbers are the same: ";

cout << k1 << ", " << k2 << endl;

// We can also restart an existing MTRand with a new seed

mtrand2a.seed( 1776 );

mtrand2b.seed( 1941 );

double l1 = mtrand2a();

double l2 = mtrand2b();

cout << "Re-seeding gives different numbers: ";

cout << l1 << ", " << l2 << endl;

// But there are only 2^32 possible seeds when we pass a

// single 32-bit integer. Since the seed dictates the

// sequence, only 2^32 different random number sequences will

// result. For applications like Monte Carlo simulation we

// might want many more. We can seed with an array of values

// rather than a single integer to access the full 2^19937-1

// possible sequences.

MTRand::uint32 seed[ MTRand::N ];

for( int n = 0; n < MTRand::N; ++n )

seed[n] = 23 * n; // fill with anything

MTRand mtrand3( seed );

double m1 = mtrand3();

double m2 = mtrand3();

double m3 = mtrand3();

cout << "We seeded this sequence with 19968 bits: ";

cout << m1 << ", " << m2 << ", " << m3 << endl;

// Again we will have the same sequence every time we run the

// program. Make the array with something that will change

// to get unique sequences. On a Linux system, the default

// auto-initialization routine takes a unique sequence from

// /dev/urandom.

// For cryptography, also remember to hash the generated

// random numbers. Otherwise the internal state of the

// generator can be learned after reading 624 values.

// We might want to save the state of the generator at an

// arbitrary point after seeding so a sequence could be

// replicated. An MTRand object can be saved into an array

// or to a stream.

MTRand mtrand4;

// The array must be of type uint32 and length SAVE.

MTRand::uint32 randState[ MTRand::SAVE ];

mtrand4.save( randState );

// A stream is convenient for saving to a file.

ofstream stateOut( "state.dat" );

if( stateOut )

{

stateOut << mtrand4;

stateOut.close();

}

unsigned long n1 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long n2 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long n3 = mtrand4.randInt();

cout << "A random sequence: "

<< n1 << ", " << n2 << ", " << n3 << endl;

// And loading the saved state is as simple as

mtrand4.load( randState );

unsigned long o4 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long o5 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long o6 = mtrand4.randInt();

cout << "Restored from an array: "

<< o4 << ", " << o5 << ", " << o6 << endl;

ifstream stateIn( "state.dat" );

if( stateIn )

{

stateIn >> mtrand4;

stateIn.close();

}

unsigned long p7 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long p8 = mtrand4.randInt();

unsigned long p9 = mtrand4.randInt();

cout << "Restored from a stream: "

<< p7 << ", " << p8 << ", " << p9 << endl;

// We can also duplicate a generator by copying

MTRand mtrand5( mtrand3 ); // copy upon construction

double q1 = mtrand3();

double q2 = mtrand5();

cout << "These two numbers are the same: ";

cout << q1 << ", " << q2 << endl;

mtrand5 = mtrand4; // copy by assignment

double r1 = mtrand4();

double r2 = mtrand5();

cout << "These two numbers are the same: ";

cout << r1 << ", " << r2 << endl;

// In summary, the recommended common usage is

MTRand mtrand6; // automatically generate seed

double s = mtrand6(); // real number in [0,1]

double t = mtrand6.randExc(0.5); // real number in [0,0.5)

unsigned long u = mtrand6.randInt(10); // integer in [0,10]

// with the << and >> operators used for saving to and

// loading from streams if needed.

cout << "Your lucky number for today is "

<< s + t * u << endl;

return 0;

}

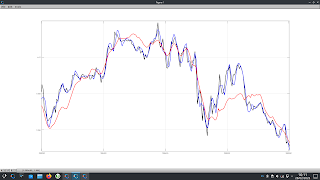

The function produces a permuted time series that preserves the trend of the original time series ( begins and ends with the same values for both the permuted and unpermuted data ) as can be seen in this screen shot of typical output, plotted using

Gnuplot,

where the yellow is the real ( in this case S & P 500 ) data and the red and blue bars are a typical example of a single permutation run. This next screen shot shows that part of the above where the two series overlap on the right hand side, so that the details can be visually compared.

The purpose and necessity for this will be explained in a future post, where the planned tests will be discussed in more detail.